|

SON HOUSE

APPLICATION FOR ACCEPTANCE –

BEALE STREET BRASS NOTE WALK OF FAME

Jeff Droke – 2011

If there was ever a living and

breathing personification of the blues, it would have to be

in the form of the one and only Eddie James “Son” House. He

was one of the musical genre’s pioneers and his influence

has been passed down to later generations via such acclaimed

protégés as Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters.

It is hard to imagine how either Beale Street or the blues

would have progressed through time had it not been for the

emotional heart-felt music produced by House. Throughout

the thirties, he lived in nearby Lake Cormorant in DeSoto

County and would quite often venture to Beale Street’s

Church Park to perform for tips.

In there is anyone that deserves a

brass note on Beale Street, it is the “Pride of Lake

Cormorant”, Eddie James “Son” House.

“Son House spoke to me

in a thousand ways…..” Jack White

|

|

BEGINNINGS

Oh, I went in my

room, I bowed down to pray

Till the blues come along, and they blowed my spirit away

- Preachin’ Blues

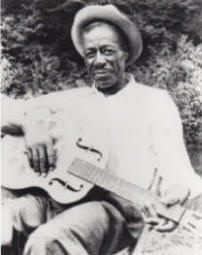

There

are very few artists in the history of recorded music that

have possessed the raw passion and performed with the

intense emotional energy of Eddie James “Son” House, Jr.

Along with fellow Mississippi Delta native Charlie Patton,

House helped lay out the framework for the music that would

become known as “The Delta Blues”. The timeless music

created by both House and Patton would directly influence

blues legends Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters and also serve

as inspiration for later-day artists such as the Rolling

Stones, Led Zeppelin and the White Stripes. In 1970,

Melody Maker Magazine writer Paul Oliver described

House’s legacy as follows: “for many, he was a bluesman from

who could be drawn a direct line - House-Robert

Johnson-Muddy Waters-Elmore James and so on. For the blues

enthusiasts the living witness to the Mississippi tradition,

he is virtually set apart from normal critical appraisal.

Playing partner to Charlie Patton and Willie Brown,

inspiration of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, he is a key

figure in the story of Delta blues with a timeless

reputation”. When interviewed by blues historian Dick

Waterman, White Stripes front man Jack White stated he had

only one influence and that was Son House. The self-titled

debut album by the White Stripes, released in 1999, was

dedicated to House. There

are very few artists in the history of recorded music that

have possessed the raw passion and performed with the

intense emotional energy of Eddie James “Son” House, Jr.

Along with fellow Mississippi Delta native Charlie Patton,

House helped lay out the framework for the music that would

become known as “The Delta Blues”. The timeless music

created by both House and Patton would directly influence

blues legends Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters and also serve

as inspiration for later-day artists such as the Rolling

Stones, Led Zeppelin and the White Stripes. In 1970,

Melody Maker Magazine writer Paul Oliver described

House’s legacy as follows: “for many, he was a bluesman from

who could be drawn a direct line - House-Robert

Johnson-Muddy Waters-Elmore James and so on. For the blues

enthusiasts the living witness to the Mississippi tradition,

he is virtually set apart from normal critical appraisal.

Playing partner to Charlie Patton and Willie Brown,

inspiration of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, he is a key

figure in the story of Delta blues with a timeless

reputation”. When interviewed by blues historian Dick

Waterman, White Stripes front man Jack White stated he had

only one influence and that was Son House. The self-titled

debut album by the White Stripes, released in 1999, was

dedicated to House.

House was born March 21, 1902 in

Riverton, Mississippi, a small delta town just outside

Clarksdale. His father served as a deacon with the Alan

Chapel Baptist Congregation and his staunch church-going

mother forbade her child from listening to secular music of

any kind, especially the blues. As a child, House attendee

Sabbath School at Morning Star Baptist Church on Mississippi

State Highway One, just west of Clarksdale. During his

youth, House was determined to spread the gospel as an

ordained minster in the Baptist Church and he preached his

first sermon at the tender age of 15. He would spend the

next few years of his young life preaching “the Word” at

various Baptist and CME churches, as his family moved

throughout the Mississippi Delta and Western Louisiana.

House remained a life-long committed Baptist and would

continue to preach on a part-time basis throughout his music

career. One of the most treasured highlights of a Son House

performance during the sixties and seventies was his soul

stirring acapella version of the traditional gospel number

John the Revelator.

During his twenties, House began to take notice of the blues

and taught himself how to play the guitar at age 25. He

witnessed a slide guitar player named Willie Wilson perform

just outside of Clarksdale and was taken in by his

performance. House bought a

guitar for $1.50 and after a few weeks

of practice, he was joining with his mentor Wilson in local

performances. House was impressed by Wilson’s music but his

strict upbringing in the Baptist Church weighed heavy on his

mind. The churches in Mississippi’s African-American

community took a firm stand against the “evil blues” that

was being performed at “juke joints” and plantation

parties. During that time period, many residents of the

Mississippi Delta would view those who performed music in an

environment outside of the church as being “in league with

Satan.” House’s struggle between the Baptist Church and

“sinful” blues music created an inner tension that helped to

fuel the power and tortured emotion displayed in his

performances. House stated during a July 1965 interview

with writer Julius Lester for Sing Out magazine

“Brought up in church and didn’t believe in anything else

but church, and it always made me mad to see a man with a

guitar and singing these blues and things.” |

|

It wasn’t long before House began

performing at “Juke Joints” in the Delta and gained

notoriety for his intense vocals and string-snapping guitar

accompaniments. The “Juke Joints” that populated the

Mississippi Delta during the Twenties and Thirties were

establishments where African-American workers from nearby

share cropper plantations could come and unwind on the

weekends after spending the week performing field work. The

blues musicians performed songs that struck a cord within

the soul of these workers with their tales of lost love and

hard times. The “Juke Joints” of the Mississippi Delta

provided their patrons with worldly pleasures that were

unimaginable to those that had endured the hardship of

slavery during the previous century.

Unfortunately, the patrons at these

“Juke Joints” could sometimes become a bit rowdy and during

a Son House performance at Lyon, Mississippi during 1927,

that was the case. An enraged man began firing a gun inside

the establishment and House killed the attacker in self

defense. A Coahoma County Court Judge in Clarksdale,

sentenced House to 15 years of hard labor at the Mississippi

State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm), an 18,000 acre work

facility located in Sunflower County. He served two years

of his manslaughter sentence before being granted an early

release in 1929.

|

|

PARAMOUNT RECORDINGS

I said, soon

every mornin' I lie's feelin' sick and bad

Thinkin' about the old time, baby, that I once have had

-Son Goin’ Down

After

his release from Parchman, Son House moved farther north up

US Highway 61 to the small Tunica County town of Lula. There

he began a musical collaboration with the man known as the

“Father of the Delta Blues”, Charlie Patton. Patton lived

on the Kirby Plantation and was an established blues legend

throughout the Southeast. Patton possessed a rhythmic style

that would set the standard for all Delta Blues guitarists

to follow. House and Patton became close friends that

shared a mutual admirations of the blues, alcohol and

performing. During May 1930, Patton took House along with

fellow blues musicians Willie Brown and Louis Johnson to

Paramount Recording in Grafton, Wisconsin. Paramount had

sat up shop in the old Wisconsin Chair Factory, located on

the banks of the Milwaukee River. At the time, Paramount

Recording was one the leading recording services for

African-American talent and was responsible for about

one-quarter of the genre’s output. As sales progressed, the

company was able to construct a new damp-stone studio during

the fall of 1929. After

his release from Parchman, Son House moved farther north up

US Highway 61 to the small Tunica County town of Lula. There

he began a musical collaboration with the man known as the

“Father of the Delta Blues”, Charlie Patton. Patton lived

on the Kirby Plantation and was an established blues legend

throughout the Southeast. Patton possessed a rhythmic style

that would set the standard for all Delta Blues guitarists

to follow. House and Patton became close friends that

shared a mutual admirations of the blues, alcohol and

performing. During May 1930, Patton took House along with

fellow blues musicians Willie Brown and Louis Johnson to

Paramount Recording in Grafton, Wisconsin. Paramount had

sat up shop in the old Wisconsin Chair Factory, located on

the banks of the Milwaukee River. At the time, Paramount

Recording was one the leading recording services for

African-American talent and was responsible for about

one-quarter of the genre’s output. As sales progressed, the

company was able to construct a new damp-stone studio during

the fall of 1929.

On May 28, 1930, House, accompanied by

only his steel-bodied National Resonator guitar, recorded

eight songs: The Dry Spell Blues (parts 1 & 2),

Preachin’ the Blues (parts 1 & 2), My Black Mama

(parts 1 & 2), Clarksdale Moan, and Mississippi

County Farm. At that time the only method available for

recording was the direct-to-disc method which produced a

master copy used for subsequent stampings. The records

produced from the stampings would spin at 78 revolutions per

minute and had a total recording time limit of about four

and a half minutes. The time limitation inherent to this

process is the reason why three of House’s songs were

divided into two parts.

House’s Paramount recordings provide

testament to his intense guitar technique and powerful vocal

styling. He would play the songs utilizing his right thumb

to sound the bass note with sting-snapping power while

attacking the other higher stings to obtain his trademark

sound. House used a copper slide on his left ring finger to

articulate the higher notes of each song performed. It is

also important to note that slide guitar playing generally

requires a somewhat gentle touch and House’s playing style

was anything but gentle. The fact that he was able to

achieve the proper slide sound with his left hand while

hammering the strings with his right hand is in itself quite

a feat.

In 1941, when Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax

questioned blues guitar great Muddy Waters as to who was the

best guitarist, Robert Johnson or Son House, Waters replied

“I think they were both equal.” Waters went on to state

“Whenever I heard he

was gonna play somewhere, I followed

after him and stayed watching him. I learned how to play

with the bottleneck by watching him for about a year.” |

|

Paramount’s recorded output was

notorious for inferior sound quality and unfortunately, none

of the Son House recordings sold well. House stated in a

1968 interview with Bob West “…we didn’t get much out of our

first recordings. My check was $40. I remember it was $40

and expenses, which was a lot of money then. I was a big

shot”. The country’s economic depression also attributed

to a general decline in music sales and very few of House’s

original Paramount Recordings exist. As the decade

progressed, changing musical tastes among African-Americans

in the Southeastern United States would also help to signal

an end to the era of the Delta Blues.

Kirby Plantation, Charlie Patton’s old

home, is still in operation and is now called the

Kirby-Willis Plantation. It is located on US Highway 61 in

Robinsonville, Mississippi, in the shadows of the Tunica

Casinos, themselves a somewhat glitzy version of the fabled

“Juke Joints”. Unfortunately, Paramount Recording fell

victim to the Great Depression and ceased recording

activities in 1932. All that remains of the studio used by

the four Mississippi bluesmen is the stone foundation. It

is located along with a historical landmark sign in Grafton

at the corner of Falls Road and 12th Avenue.

|

|

ROBERT JOHNSON AND THE

CROSSROADS LEGEND

You just bear this is

mind, a true friend is hard to find

Don’t you mind, people grinnin’ in your face

-Grinnin In Your Face

As

the Thirties progressed, House moved to the north delta town

of Robinsonville. “When we came back from recording, I went

back down to Lula and stayed about a couple of weeks, and

then I came right back to Robinsonville where Willie was”

stated House in his 1965 interview with Sing Out!

Magazine’s Julius Lester “He was my commentor. He like to

comment. He never liked to sing much. He was a good

commentor.” House and his close friend Willie Brown were

able to make a living by performing at parties and

plantations in the Robinsonville area in the early

thirties. During that time period, the two musicians

befriended a young harmonica player named Robert Johnson.

On the weekends, House, Willie Brown and Johnson would

travel to Memphis and perform at Church Park on Beale Street

for tips. Johnson had become so taken with House’s guitar

playing ability, that he switched his instrument of choice

from harmonica to guitar. Unfortunately, the future blues

legend did not come quick in mastering his new instrument

and would be chided by his two mentors when they were

drinking. As

the Thirties progressed, House moved to the north delta town

of Robinsonville. “When we came back from recording, I went

back down to Lula and stayed about a couple of weeks, and

then I came right back to Robinsonville where Willie was”

stated House in his 1965 interview with Sing Out!

Magazine’s Julius Lester “He was my commentor. He like to

comment. He never liked to sing much. He was a good

commentor.” House and his close friend Willie Brown were

able to make a living by performing at parties and

plantations in the Robinsonville area in the early

thirties. During that time period, the two musicians

befriended a young harmonica player named Robert Johnson.

On the weekends, House, Willie Brown and Johnson would

travel to Memphis and perform at Church Park on Beale Street

for tips. Johnson had become so taken with House’s guitar

playing ability, that he switched his instrument of choice

from harmonica to guitar. Unfortunately, the future blues

legend did not come quick in mastering his new instrument

and would be chided by his two mentors when they were

drinking.

“We'd all play for the Saturday night

balls and there’d be this little boy standing around. That

was Robert Johnson.” stated House to Julius Lester “And when

we'd get a break and want to rest some, we'd set the guitars

up in the corner and go out in the cool. Robert would watch

and see which way we’d gone and he would pick one of them

up. And such another racket you never heard! It'd make the

people mad, you know. They’d come out and say, Why don't

y'all go in there and get that guitar away from that boy!

He's running people crazy with it."

In 1931, Johnson moved back to his

birthplace of Hazlehurst, Mississippi, where he began to

become an accomplished player through hours and hours of

practice. When he returned to Robinsonville, House was

amazed at the musical transformation that Johnson had gone

through. House has been quoted as stating “He sold his soul

to the devil to get to play like that.” Even Johnson seemed

to help popularize the Faustian myth by embellishing stories

of how his guitar prowess transformed so dramatically.

House’s protégé went on to become notably regarded as the

most important figure in blues music. Rolling Stone guitar

player Keith Richard is quoted in the liner note for the

1990 Robert Johnson box set “You want to know how good the

blues can get? Well, this is it."

|

|

LIFE IN THE DELTA

Yes, I went in my

room, and I said, and I sat down and I cried,

Yes, I didn't have no blues, but I just wasn't satisfied

- Downhearted Blues

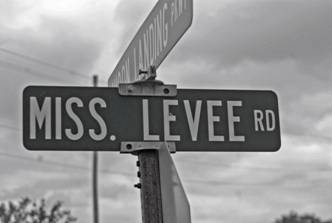

In

1932, Son House married Evie Goff (June 13, 1905 – April 15,

1999), a young lady that was employed as a cook by a Lake

Cormorant, Mississippi doctor. House told Betsy Bues during

a July 1964 interview “I stole her right out of the doctor’s

kitchen”. This union would be House’s fifth and final

marriage. The couple lived in Lake Cormorant, a small

Highway 61 town located just south of Memphis in Desoto

County. During this time, House worked at various

farm-related jobs on the cotton plantations that surrounded

the area. House and Willie Brown also continued to perform

in Tunica County, DeSoto County and Memphis for the

remainder of the decade. On many weekends, House would

play the “devil’s music” during performances at Lake

Cormorant’s Clack’s store on Saturday night and then preach

God’s Holy word on Sunday mornings at the adjacent Samuel

Baptist Church. In

1932, Son House married Evie Goff (June 13, 1905 – April 15,

1999), a young lady that was employed as a cook by a Lake

Cormorant, Mississippi doctor. House told Betsy Bues during

a July 1964 interview “I stole her right out of the doctor’s

kitchen”. This union would be House’s fifth and final

marriage. The couple lived in Lake Cormorant, a small

Highway 61 town located just south of Memphis in Desoto

County. During this time, House worked at various

farm-related jobs on the cotton plantations that surrounded

the area. House and Willie Brown also continued to perform

in Tunica County, DeSoto County and Memphis for the

remainder of the decade. On many weekends, House would

play the “devil’s music” during performances at Lake

Cormorant’s Clack’s store on Saturday night and then preach

God’s Holy word on Sunday mornings at the adjacent Samuel

Baptist Church.

In August 1941, the famed folklorist

Alan Lomax joined together with faculty from Nashville’s

Fisk University in effort to record some of the remaining

Delta Blues musicians, especially Robert Johnson. Lomax,

Assistant in Charge of the Archive of Folk Song of the

Library of Congress, had experience in recording blues and

folk musicians throughout the Southeastern United States.

Lomax set up his recording device at Clack’s Store in Lake

Cormorant, a small establishment that served as a railroad

depot, commissary and farm supply store. The old Illinois

Central’s Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad line between

Memphis and Baton Rouge ran directly behind the store and

the noise created by passing trains can be heard in some of

the Clack’s Store recordings. House was accompanied by

Willie Brown (guitar), LeRoy Martin (harmonica) and Fiddlin’

Joe Martin (mandolin) during the recording sessions. The

musicians recorded Camp Hollers, Delta Blues, Fo’ Clock

Blues, Government Fleet Blues, Levee Camp Blues, Shetland

Pony Blues and Walking Blues.

In July 1942, Lomax returned to the

Delta and recorded an unaccompanied House in nearby

Robinsonville. That recording session produced American

Defense, Am I Right or Wrong, Country Farm Blues, Depot

Blues, The Jinx Blues (parts 1 & 2), Low Down Dirty Dog

Blues, My Black Women and Pony Blues. Lomax has

been quoted as stating “Of all my times with the blues, this

was the best one”

|

|

In 1943, House moved to Rochester, New

York and gained employment in railcar construction for the

New York Central Railroad. The Second World War had created

quite a number of industrial and transportation jobs in the

country and it also opened up a whole new world of economic

opportunity for African-Americans. House wrote Willie Brown

about his new career and encouraged Brown to move north to

join him. Brown remained in Lake Cormorant and died of

heart disease on December 30, 1952 in Tunica at age 52.

Brown is buried at Good Sheppard Church Cemetery in

Pritchard, Mississippi.

The forties were a time of drastic

change in America society. The Great Depression had just

ended and the country found itself fighting brutal wars in

both Europe and the Pacific. The technology and cultural

changes brought about by the Second World War could fill

volumes. In one decade, America’s air military assets went

from 160 mph biplanes to 700 mph jets. Music listening

patterns may not have changed that drastically but by the

end of the war, the Delta Blues was looked at as “old

people’s music”. The younger generation was more interested

in songs with a faster beat and artists like Son House

retired from sight.

Clack’s

Store was located on the west side of Old Highway 61 just

south of Harrah’s Parkway. The building was demolished in

1993 as the area underwent a major transformation with the

arrival of the Tunica Casinos. The photo at left shows the

land that was once occupied by Clack’s store. The renovated

Samuel Baptist Church is visible in the background. The

Illinois Central route that ran behind the store is also

abandoned with little recognizable trace remaining. The

sign from Clack’s Grocery now resides at the Delta Blues

Museum in Clarksdale. Clack’s

Store was located on the west side of Old Highway 61 just

south of Harrah’s Parkway. The building was demolished in

1993 as the area underwent a major transformation with the

arrival of the Tunica Casinos. The photo at left shows the

land that was once occupied by Clack’s store. The renovated

Samuel Baptist Church is visible in the background. The

Illinois Central route that ran behind the store is also

abandoned with little recognizable trace remaining. The

sign from Clack’s Grocery now resides at the Delta Blues

Museum in Clarksdale.

|

|

REDISCOVERY

When you hear me

singin' my ol' lonesome song

These hard times can't last up so very long

- Dry Spell Blues

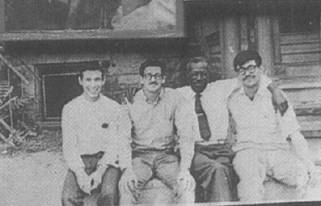

In

the mid-sixties as many American’s fell victim to the

British Invasion, there was a small group of music fans

searching diligently for the past. Included in this group

were Nick Perls, Richard Waterman and Philip Spiro (pictured

at left with House), all hailing far from the fertile soil

of the Mississippi Delta. Some music historians might

refer to their search as a “Beatles Backlash”, since the Fab

Four and its seemingly endless clones were clogging the

airwaves. As the sixties progressed, a folk revival took

root and along with it came a renewed interest in the blues.

Unfortunately, many bluesmen from twenties and thirties had

either died or simply disappeared from the public and

settled into mundane normal lives. In 1961, there was a

ground shed event that would help bring about a rebirth of

interest in the Delta Blues with the release of the Robert

Johnson LP King of the Delta Blues. Johnson, a

disciple of both Charlie Patton and Son House, had recorded

the songs during 1937 and they were finally making their way

into public some 24 years later. The early sixties were a

time of burgeoning change in both American and British

societies and Johnson’s recordings stood ready to influence

the coming generation of rock musicians. In

the mid-sixties as many American’s fell victim to the

British Invasion, there was a small group of music fans

searching diligently for the past. Included in this group

were Nick Perls, Richard Waterman and Philip Spiro (pictured

at left with House), all hailing far from the fertile soil

of the Mississippi Delta. Some music historians might

refer to their search as a “Beatles Backlash”, since the Fab

Four and its seemingly endless clones were clogging the

airwaves. As the sixties progressed, a folk revival took

root and along with it came a renewed interest in the blues.

Unfortunately, many bluesmen from twenties and thirties had

either died or simply disappeared from the public and

settled into mundane normal lives. In 1961, there was a

ground shed event that would help bring about a rebirth of

interest in the Delta Blues with the release of the Robert

Johnson LP King of the Delta Blues. Johnson, a

disciple of both Charlie Patton and Son House, had recorded

the songs during 1937 and they were finally making their way

into public some 24 years later. The early sixties were a

time of burgeoning change in both American and British

societies and Johnson’s recordings stood ready to influence

the coming generation of rock musicians.

Soon many listeners and critics alike

began trying to determine the source to the genius of the

fabled Robert Johnson and his brilliant recordings. Of

course, that would lead them back to his two main

influences, Charlie Patton and Son House. Unfortunately by

the time that the Delta Blues was finally beginning to reach

a larger audience, both Johnson and Patton were dead. Only

Son House would be able to provide the new generation of

fans with a glimpse into the past. Alan Wilson, a young

blues enthusiast from Cambridge, Massachusetts (who would

later himself find fame as both a guitar player and vocalist

in the quintessential blues-rock band “Canned Heat”)

encountered Memphis bluesman Bukka White, who told him that

House had last been seen in Memphis a year or so earlier.

Wilson relayed this information to another Son House devotee

also living in Cambridge, Philip Sprio.

During the summer of 1964, Sprio joined with two other young

blues enthusiasts in an effort to locate the enigmatic Son

House. New Yorkers Dick Waterman and Nick Perls joined with

Spiro and headed to Memphis in a Volkswagen in attempt to

locate House. Wilson was unable to join in the search as

prior performance commitments keep him in Cambridge. Much

to their surprise, the trio would eventually find House

close to their home, living in a third-floor walk-up

apartment at 61 Grieg Street in Rochester, New York’s Corn

Hill neighborhood. The apartment has since been torn-down

and the section of Grieg Street where House lived is

occupied by an apartment complex at 596 Clarissa Street.

|

|

When

asked in July 1964 by Betsy Bues of the Rochester

Times-Union about a comeback, House stated “That’s what

I want to do. I think it’s great. I am going to try to make

it as great as I can. And I think I can.” During the

mid-sixties, competition from America’s Interstate Highways

combined with the emerging commercial airline industry

forced the railroads into a cost-cutting mode. In 1964,

House was laid-off from the New York Central Railroad and

had taken a job at Howard Johnson’s Motel Restaurant as a

cook. The Motel is no longer standing but restaurant

(pictured above at left) is somewhat ironically called “The

Delta House” and is located at 2550 Buffalo Road in

Rochester. When

asked in July 1964 by Betsy Bues of the Rochester

Times-Union about a comeback, House stated “That’s what

I want to do. I think it’s great. I am going to try to make

it as great as I can. And I think I can.” During the

mid-sixties, competition from America’s Interstate Highways

combined with the emerging commercial airline industry

forced the railroads into a cost-cutting mode. In 1964,

House was laid-off from the New York Central Railroad and

had taken a job at Howard Johnson’s Motel Restaurant as a

cook. The Motel is no longer standing but restaurant

(pictured above at left) is somewhat ironically called “The

Delta House” and is located at 2550 Buffalo Road in

Rochester.

|

|

SECOND CHANCE

I went in my room, I

said I bowed down to pray

I said the blues came along and drove my spirit away

- Death Letter

In

1964, Richard Waterman became Son House’s manager and Alan

Wilson (pictured at left) helped House retune his musical

talents back to his glory days in the Mississippi Delta.

This compelling story of second chance received feature

coverage in Newsweek Magazine. Soon House was

featured at the Newport Folk Festival and had a recording

contract with Columbia Records. “Son House had not really

played guitar much since the forties” stated Waterman in May

2011, “Alan Wilson would set down with Son and refresh his

memory on how he had played each song recorded during the

thirties and forties.” Waterman recalls an exuberant House

proclaiming “I’m getting my recollection back!” as he began

to once again play the tunes from the past. In

1964, Richard Waterman became Son House’s manager and Alan

Wilson (pictured at left) helped House retune his musical

talents back to his glory days in the Mississippi Delta.

This compelling story of second chance received feature

coverage in Newsweek Magazine. Soon House was

featured at the Newport Folk Festival and had a recording

contract with Columbia Records. “Son House had not really

played guitar much since the forties” stated Waterman in May

2011, “Alan Wilson would set down with Son and refresh his

memory on how he had played each song recorded during the

thirties and forties.” Waterman recalls an exuberant House

proclaiming “I’m getting my recollection back!” as he began

to once again play the tunes from the past.

The legendary bluesman would make a

triumphant return to the studio during April 12-14, 1965

accompanied by Alan Wilson. House and Wilson recorded 21

tracks at New York’s Columbia Recording Studio, located at

207 East 30th Street. Waterman states “It was a

solo record for the most part.” Alan plays second guitar on

Empire State Express and harp on Levee Camp Moan.”.

Wilson was 21 years old at the time of the recordings and

would later be called “the greatest harmonica player ever”

by blues legend John Lee Hooker. House utilized a National

metal-bodied resonator guitar and a copper slide during the

sessions.

The album contained nine tracks and

would be appropriately called Father of the Folk Blues

(Columbia 2417). It was produced by John Hammond, a

Columbia producer who was responsible for the 1961 Robert

Johnson LP King of the Delta Blues Singers. The

entire output of the 1965 Columbia recording session would

be released in CD format by Sony during 1992.

Blues historian Richard Waterman

recalls a May 1965 encounter between the Rolling Stones and

Son House. “Mr. House and I were visiting Los Angeles in

1965 when we found out that Howlin’ Wolf was in town

recording a ABC Television show called “Shindig” stated

Waterman, “When we got there, Wolf was excited to see House

and was soon hugging his old friend. When Brian Jones

approached to inquire who the older gentleman was, I stated

it was Son House.” Jones, an avid blues historian himself

retorted back to his band mates “It’s bloody Son House!”

House began touring across both the

United States and Europe during the mid-sixties and early

seventies. House’s comeback performances represented a

vital link between the early stages of recorded music and

the new generation of musicians it had spawned. In a

brief few months, House had gone from relative obscurity to

performing in front of packed houses filled with thousands

of young appreciative fans. House outlived

contemporaries like Willie Brown and Charlie Patton,

second-generation protégés Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters,

as well as third-generation blues guitarists Jimi Hendrix

and Duane Allman.

House performed his last concerts at

Rochester’s Genesee Co-Op on Monroe Ave during 1976.

As his health faded, House and his wife moved to Detroit to

be close to their relatives. He spent his final years

living sedately in an apartment at 14201 Second Street in

the Highland Park neighborhood of Detroit. The

legendary bluesman would go to meet his maker on October 19,

1988 at Harper University Hospital not far from the western

banks of the Detroit River.

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balfour, Alan, Booklet Notes to Son

House - John The Revelator - The 1970 London Session –

(Liberty LBS-83391, April 1992)

Cheseborough, Steve, Blues

Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues (University

Press of Mississippi, 2009)

Komara, Edward, Blues in the Round –

Black Music Research Journal (University of Illinois

Press, 1997)

Rothman, Michael, Son House Now: An

Afternoon With The Father Of Country Blues) (Living

Blues Magazine, July 1974)

Wardlow, Gayle, Chasing that devil

music (Backbeat Books, 1998)

|

|